for registering black folks to vote

some of the people Carolyn Daniels took in in the 1960s are still alive

linkAs SNCC formed in southwest Georgia, drawing students from the Northeast into the heart of the South, Daniels’ two-bedroom house became their headquarters. “There is always a ‘mama,’” Sherrod noted in The Making of Black Revolutionaries, the autobiography of SNCC Executive Secretary James Forman. “She is usually a militant woman in the community, outspoken, understanding, and willing to catch , having already caught her share.” In Terrell, Carolyn Daniels, he said, “is the ‘mama’ for us there.”

Daniels was willing to catch , and catch she did. Holsaert, the SNCC worker who lived with Daniels in the summer of 1962, remembers the flashy red and white Chevrolet Impala that Daniels would take SNCC students canvassing in. “It was a big, showy car that was an act of defiance, really, on her part,” Holsaert said. Four years earlier, as Daniels was well aware, Dawson police officer Weyman B. Cherry beat to death a Black resident, James Brazier, for having the temerity to purchase a new Chevrolet Impala.

Daniels taught people at her church how to register to vote and held her own voter education classes supported by King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. When white segregationists burned down the churches where Daniels taught in Terrell and nearby Lee County, she moved her classes to makeshift tents.

In September 1962, night riders fired shots into Daniels’ cinder-block home. Two SNCC workers were hit: Prathia Hall in the finger and Jack Chatfield in the arm.

“I got much of my courage and strength from her,” says Willie Ricks, also known as Mukasa Dada. “Just by being in that house, going in that house, and sleeping in that house, it took a lot of the fear out of me.”

One night, in December 1963, Daniels was home alone, lying in bed, when she heard footsteps and the slam of car doors. Then the shooting began. Daniels rolled under her bed. A bomb thrown through a window landed beside her but failed to detonate. When the shooting stopped, Daniels realized she had taken a bullet in the foot and went to the hospital. While she was there, the bomb exploded.

The entire house was destroyed. There was a massive hole in the ground where her bed had been, and slats from the roof lay around the rubble like fallen soldiers. But, in Daniels’ words, “we just kept going.” She rebuilt. And then she welcomed back the organization and students whose work had made her house a target.

Holsaert recalls the contrast between the place that hated them and the person who inspired them. It was “a rural, isolated, segregationist, violent setting,” she says. “And yet this spirit.”

down to the present day

another awesome Michael Harriot history thread

https://x.com/michaelharriot/status/1838744691606741005

don't you dare teach the troops about their government's racist ery

Trumpy CRT basically erases minorities from the story

They should most def learn about their job at hand. Our government isn't here to teach history. These soldiers can learn that in college with their GI bill.

Why wouldn't airmen learn about the history of the Air Force? This is stupid.

Does not exist in Europe

Our team our way or ostracized

Which team?

In this case Central Europe

So there are no competing political parties?

the name of the painting is "Critical Race Theory"

Whitewashing probably is a full time job now.

Trump is breaking the law 24/7, there's a lot to discuss

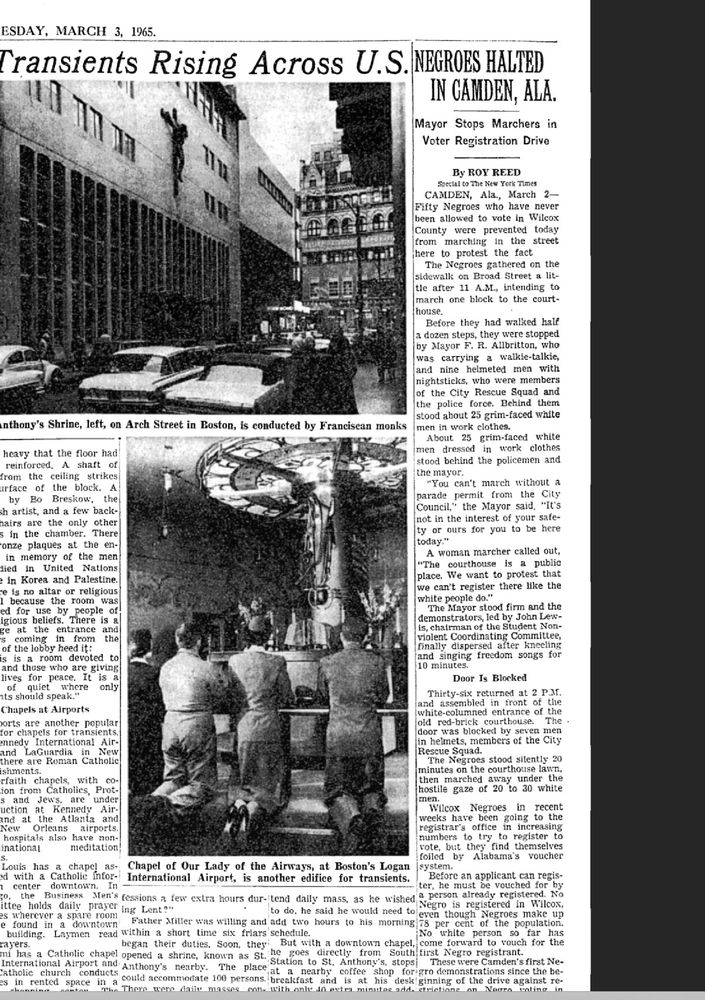

60 years ago

John Lewis was leading a march in Camden County, AL, which then was 78% black and had zero black registered voters

Civil rights and voting rights legislation that were passed over the next two years magically and instantly dispelled all racism in the USA -- forever

Except for one kind.

Racism against white people is the only kind that exists now, or is officially recognized by our government.

There are currently 1 users browsing this thread. (0 members and 1 guests)